Truth in Crisis — Part I

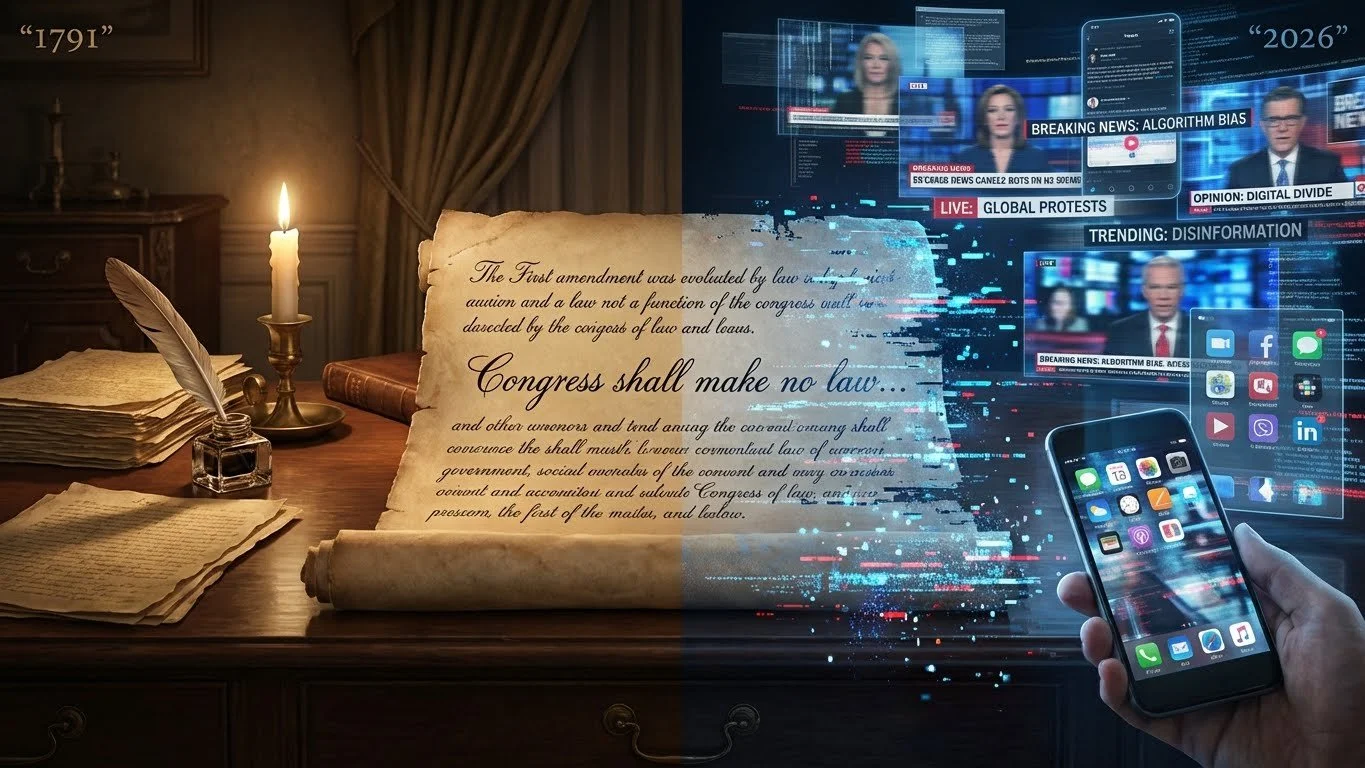

1791 protected speech from government power. 2026 tests whether truth can survive industrial deception.

The First Amendment Wasn’t Built for This

The First Amendment is one of the greatest achievements in human history. It protects dissent, guards against tyranny, and ensures that those in power can be challenged without fear of government reprisal. It is foundational to American democracy—and indispensable to a free society.

But it was not built for the world we now inhabit.

When the First Amendment was written in the late 18th century, “the press” meant printed pamphlets and newspapers. Information traveled slowly. Distribution took days or weeks. Reach was local or regional. Editors were identifiable. Accountability—while imperfect—was real. Errors could be challenged. Falsehoods could be rebutted. Debate had time to breathe.

The framers were protecting political dissent from government suppression. They were not designing a system for instantaneous, global, profit-driven influence machines capable of shaping reality itself.

That distinction matters.

Today, information moves at the speed of light. Falsehoods travel faster than verification, faster than correction, and faster than any legal remedy. The constitutional system assumes time exists for rebuttal and debate. In the modern media ecosystem, damage is often done before truth can respond.

This is not a failure of free speech. It is an unintended consequence of its success.

Over time, three fundamental changes have reshaped the information landscape in ways the Constitution could not have anticipated.

First, speed without friction.

The framers assumed that bad ideas could be countered by better ones. That assumption relied on time—time for scrutiny, time for response, time for reason to prevail. Today, a false claim can reach millions in seconds, amplified by algorithms designed to reward outrage rather than accuracy. Retractions, corrections, and fact-checks rarely travel as far or as fast as the original lie.

Second, entertainment disguised as journalism.

The First Amendment protects speech. Courts protect opinion. Modern media organizations have learned to exploit this distinction by presenting opinion programming using the visual language and authority of journalism—news desks, chyrons, breaking-news graphics—while later claiming “entertainment” when challenged. Viewers are told to treat the content as news, but courts are asked to treat it as performance.

This is not classical free speech. It is identity laundering.

Third, scale without responsibility.

The framers assumed speech power was relatively diffuse. No single voice could dominate national discourse. Today, a handful of media outlets and online personalities reach tens of millions of people daily, shaping political behavior, public perception, and even democratic outcomes—often with no meaningful obligation to correct known falsehoods.

The First Amendment was designed to protect the speaker from the state.

It was not designed to protect the public from systematic deception.

That gap has grown enormous.

This moment did not arise because Americans value free speech too much. It arose because our legal framework has not evolved alongside the information ecosystem it now governs. The result is a system where intentional deception can flourish, so long as it is labeled “opinion,” monetized effectively, and insulated by wealth and legal complexity.

This is not about censorship. It is about classification, accountability, and civic responsibility.

Democracy does not require agreement. It requires a shared factual baseline—a common understanding of what is real. Without that foundation, debate collapses into tribalism, elections become identity battles, and anger replaces deliberation.

History offers a warning here. Democracies do not typically fall because citizens stop caring. They fall when truth becomes optional, when reality fractures, and when lies carry no consequence.

The framers of the Constitution could not have foreseen an information ecosystem where entertainers masquerade as journalists, where falsehoods are monetized at scale, and where millions are misled in real time. That does not diminish the First Amendment. It challenges us to take it seriously enough to confront its unintended consequences.

Free speech was meant to protect dissent—not to shield disinformation at industrial scale.

This is the question now before us:

If democracy depends on shared truth, and shared truth has collapsed, what responsibility does the Constitution have to evolve?

Part II will examine how modern media organizations legally insulate disinformation—and why existing safeguards have failed to protect the public.